How we’re using projects to build projects

At GitHub we use GitHub to build our own products, and the new projects experience is no different. Check out how our team uses projects to build powerful project planning for developers.

At GitHub, we use GitHub to build our own products, whether that be moving our entire Engineering team over to Codespaces for the majority of GitHub.com development, or utilizing GitHub Actions to coordinate our GitHub Mobile releases. And while GitHub Issues has been a part of the GitHub experience since the early days and is an integral part of how we work together as Hubbers internally, the addition of powerful project planning has given us more opportunities to test out some of our most exciting products.

In this post, I’m going to share how we’ve been utilizing the new projects experience across our team (from an engineer like myself all the way to our VPs and team leads). We love working so closely with developers to ship requested features and updates (all of which roll up into the Changelogs you see), and using the new projects helps us stay consistent in our shipping cadence.

How we think about shipping

Our core team consists of members of the product, engineering, design, and user research teams. We recognize that good ideas can come from anywhere. Our process is designed to inspire, surface, and implement those ideas, whether they come from users, individual contributors, managers, directors, or VPs. To get the proper alignment for this group, we’ve agreed on a few guiding principles that drive what our roadmap will look like:

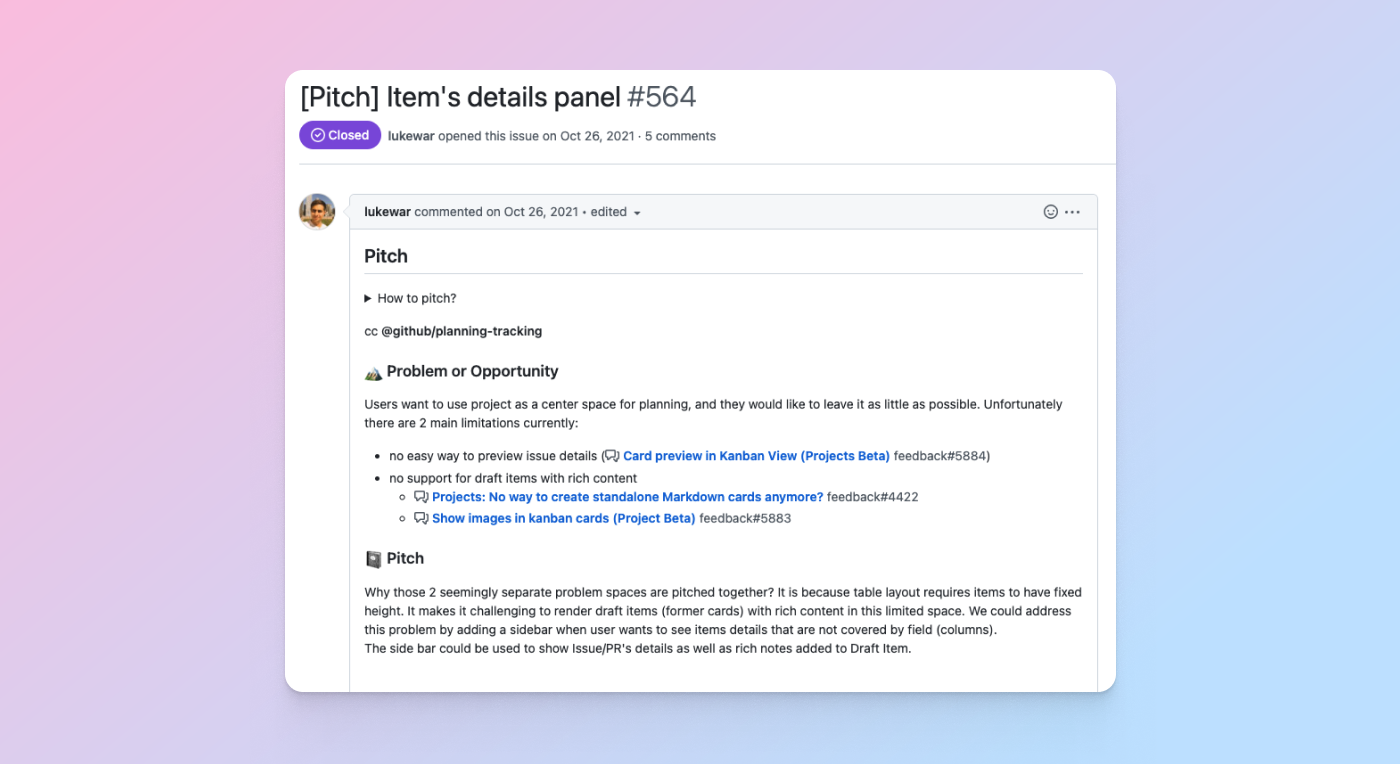

💭 The pitch: When it comes to what we’re going to work on (outside of the big pieces of work on our roadmap) people within our team can pitch ideas in our team’s repository for upcoming cycles (which we define as 6-8 weeks of work, inclusive of planning, engineering work, and an unstructured passion project week); these can be features, fixes, or even maintenance work. Every pitch must clearly state the problem it’s solving and why it’s important for us to prioritize. Some features that have come from this process include live updates, burn up charts for insights, and more. Note: these are all the changes you see as a developer, but we also have a lot of pitches come in from my fellow engineers focused around the developer experience. For example, a couple successful pitches have included reducing our CI time to 10 minutes, and streamlining our release process by switching to a ring deployment model and adding ChatOps.

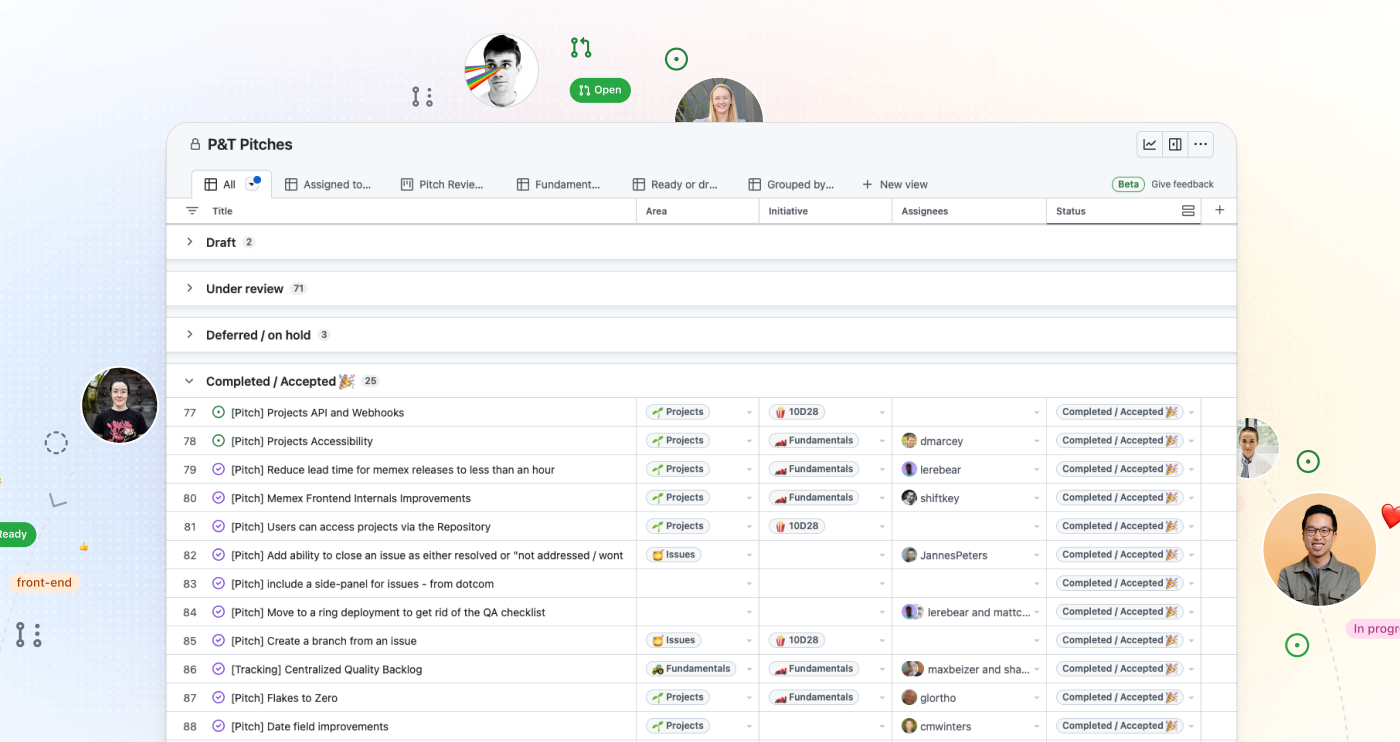

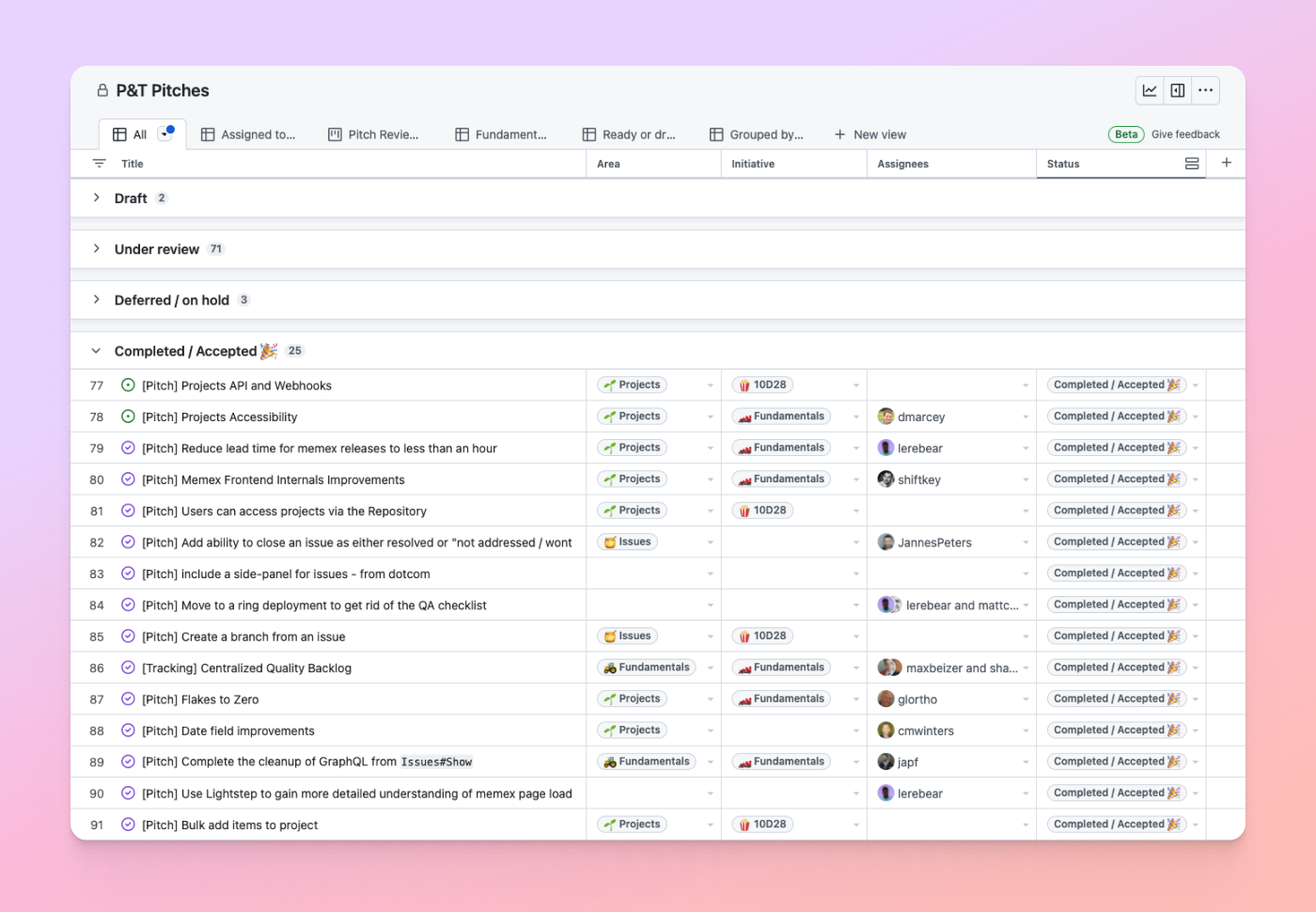

💡 In addition to using issues to propose and converse on pitches from the team, we use the new projects experience to track and manage all the pitches from the team so we can see them in an all-up table or board view.

✂ Keep it small: We knew for ourselves, and for developers, that we didn’t want to lock them into a specific planning methodology and over-complicate a team’s planning and tracking process. For us, we wanted to plan shorter cycles for our team to increase our tempo and focus, so we opted for six-week cycles to break up and build features. Check out how we recommend getting started with this approach in a recent blog post.

📬 Ship to learn: Similar to how we ship a lot of our products, we knew developers and customers were going to be heavily intertwined with each and every ship, giving us immediate feedback in both the private and public beta. Their feedback both influenced what we built and then how we iterated and continued to better the experience once something did ship. While there are so many people to thank, we’re extremely grateful for all our customers along the way for being our partners in building GitHub Issues into the place for developers to project plan.

How we used projects to do it

We love that the product we’re building doesn’t tool a specific project management methodology, but equips users with powerful primitives that they can compose into their preferred experiences and workflows. This allows for many people (not just us engineers) involved in building and developing products at GitHub (team leads, marketing, design, sales, etc.) the ability to use the product in a way that makes sense for them.

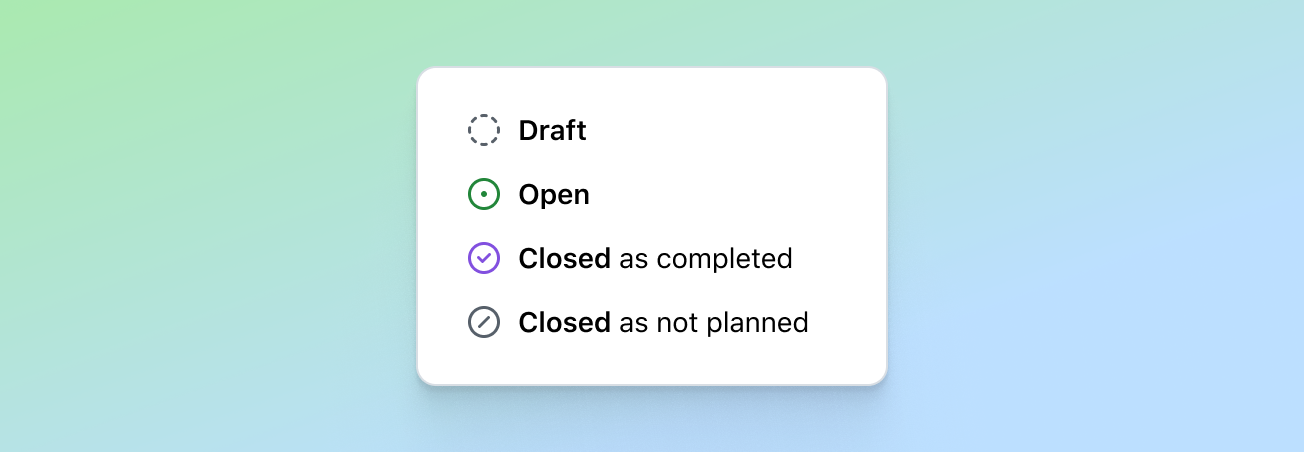

With the above principles in mind, once a pitch has been agreed upon to move forward on building, that pitch issue becomes a tracking issue in a project table or board that we convert into pieces of work that fit into an upcoming cycle. A great example of this was when we updated the GitHub Issues icons to lessen confusion among developers. This came in as a pitch from a designer on the team, and was soon accepted and moved into epic planning in which the team responsible began to track the individual pieces of work needed to make this happen.

IC approach

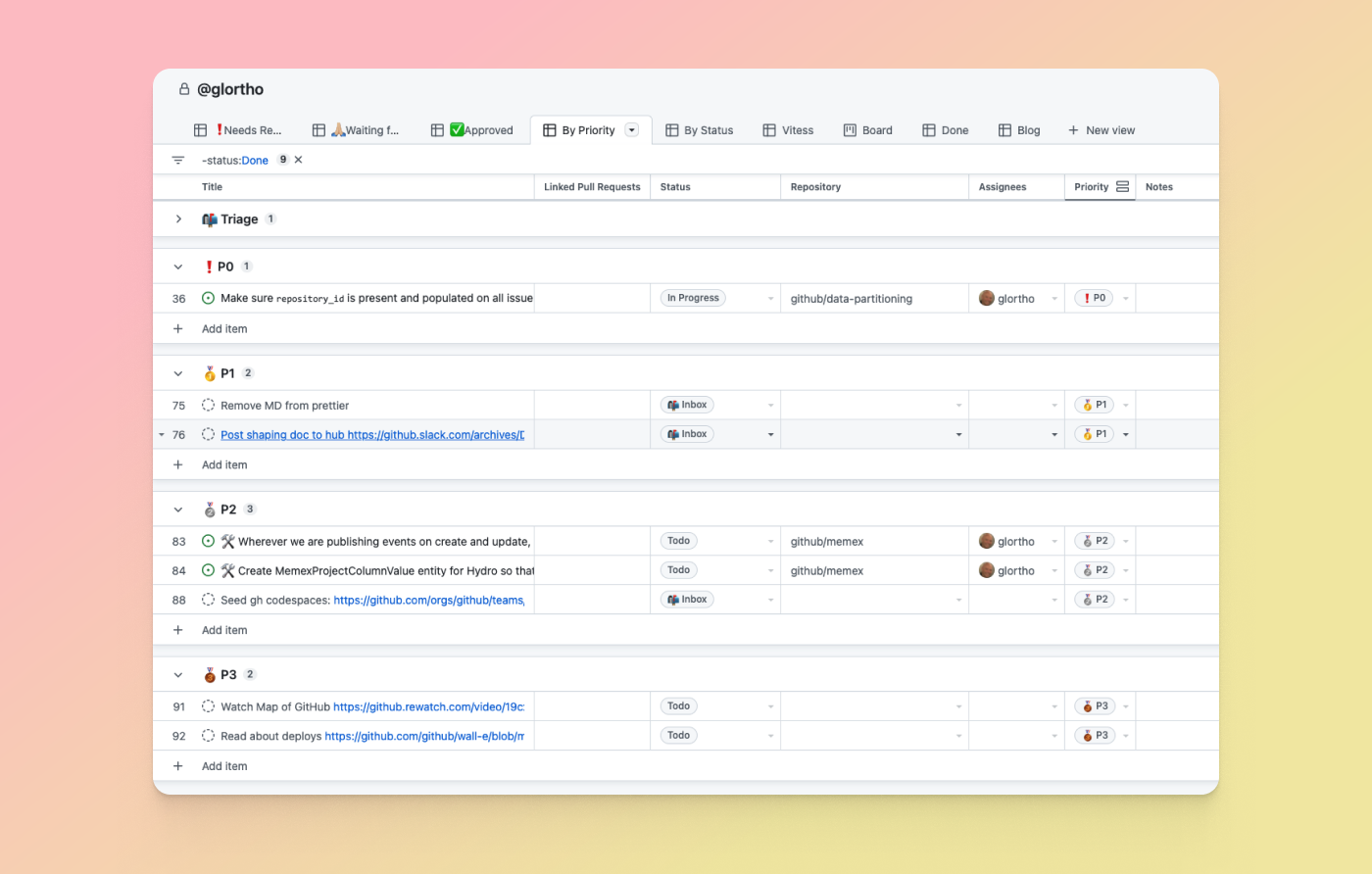

Let’s start with how my fellow engineers, individual contributors and I use projects for day-to-day development within cycles. From our perspective on any given day, we’re hyper-focused on tackling what issues and pull requests are assigned to us (fun fact: we recently added the assignee:me filter to make this even easier) in a given cycle, so we work from more individually scoped project tables or boards that stem from the larger epic and iteration tracking. Because of this, we can easily zoom out from our individual tasks to see how our work fits into a given cycle, and then even zoom out more into how it fits into larger initiatives.

💡 In addition to scoping more specifically a given table or board, engineers across our organization utilize a personal project table or board to track all the things specific to themselves like what issues are assigned to them—even work not connected to a given cycle, like open source work.

EM approach

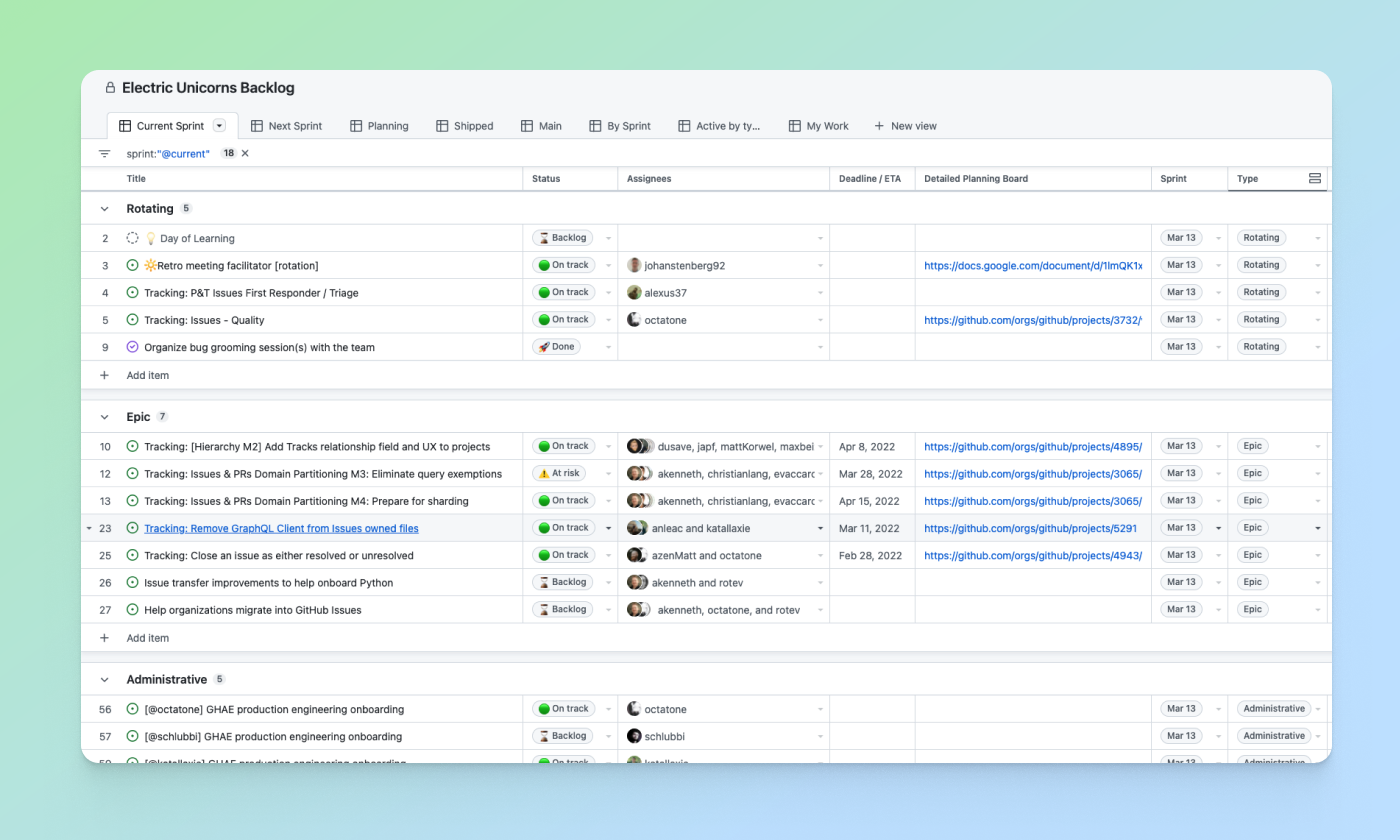

If we pull back to engineering managers overseeing those smaller cycles, they’re focused on kicking off an accepted pitch’s work, breaking it first into cycles and then into smaller iterations in which they can assign out work. A given cycle’s table or board view allows the managers to have a whole look at all members of their team and look specifically at things that are important to them, like all the pull requests that are open and quickly seeing which engineers are assigned, what pull requests have been merged, deployed, etc.

💡 Check out what this looks like in our team board.

Team lead approach

Now, if we put ourselves in the shoes of our team leads and Directors/VPs, we see that they’re using the new projects experience to primarily get the full picture of where product and feature development currently sit. They told me the main team roadmap and backlog is where they can get questions answered like:

- Which projects do we have in flight in which product area right now?

- Who’s the key decision maker for this project?

- Which engineers are working on which projects?

- Which projects are at risk and need help (progress/status)?

What’s great about this is that they can quickly glance at what’s in motion and then click into any cycles or status to get more context on open issues, pull requests, and how everything is connected.

💡 Outside of being able to check in on what’s being worked on and where the organization’s current focus is, our leads have found additional use cases that may not be applicable for an engineer like me. They use private projects for more sensitive tasks, like managing our team’s hiring, tracking upcoming start dates, making sure they’re staying on top of career development, organizational change management, and more.

Wrap-up

This is how we as the planning and tracking team at GitHub are using the very product we’re building for you to build the new projects experience. There are many other teams across GitHub that utilize the new project tables and boards, but we hope this gives you a little bit of inspiration about how to think about project planning on GitHub and how to optimize for all the stakeholders involved in building and shipping products.

What’s great about project planning on GitHub is that our focus on powerful primitives approach to project management means that there is an unlimited amount of flexibility for you and your team to play around with, and likely many, many ways we haven’t even thought about how to use the product. So, please let us know how you’re using it and how we can improve the experience!

Tags:

Written by

Related posts

How GitHub engineers tackle platform problems

Our best practices for quickly identifying, resolving, and preventing issues at scale.

GitHub Issues search now supports nested queries and boolean operators: Here’s how we (re)built it

Plus, considerations in updating one of GitHub’s oldest and most heavily used features.

Design system annotations, part 2: Advanced methods of annotating components

How to build custom annotations for your design system components or use Figma’s Code Connect to help capture important accessibility details before development.